PROBLEM WITH THIS WEBPAGE?

Report an accessibility problem

To report another problem, please contact academiccoaching@marquette.edu.

Welcome! This course has been developed by the Academic Resource Center to help you develop the executive functioning skills students need to be successful in their courses at Marquette. Without well rounded executive functioning skills, it is difficult for college students to achieve their goals. Executive functioning skills are the cognitive processes that allow us to skillfully plan, organize, prioritize, and execute. Mastering these skills allows us to set goals, make decisions, and manage our time and priorities.

By developing your executive functioning skills, you can reduce stress and successfully achieve your academic goals. This course walks you through an executive functioning curriculum, created by the Director of the Academic Resource Center and Learning Specialist, Erik Albinson, which not only focuses on time management and study strategies, but ultimately shows you how to manage stress and retain your mental capacity through strategic scheduling and energy management.

Module 1: Introduction to Executive Functioning

Please review these definitions to gain a better understanding of the executive functioning skills discussed in the upcoming modules.

Response Inhibition: The capacity to think before you act - this ability to resist the urge to say or do something allows us the time to evaluate a situation and how our behavior might impact it. In the young child, waiting for a short period without being disruptive is an example of response inhibition while in the adolescent it would be demonstrated by accepting a referee’s call without an argument.

Working Memory: The ability to hold information in memory while performing complex tasks. It incorporates the ability to draw on past learning or experience to apply to the situation at hand or to project into the future. A young child, for example can hold in mind and follow 1-2 step directions while the middle school child can remember the expectations of multiple teachers.

Emotional Control: The ability to manage emotions in order to achieve goals, complete tasks, or control and direct behavior. A young child with this skill is able to recover from a disappointment in a short time. A teenager is able to manage the anxiety of a game or test and still perform.

Sustained Attention: The capacity to maintain attention to a situation or task in spite of distractibility, fatigue, or boredom. Completing a 5Bminute chore with occasional supervision is an example of sustained attention in the younger child. The teenager is able to attend to homework, with short breaks, for one to two hours.

Task Initiation: The ability to begin projects without undue procrastination, in an efficient or timely fashion. A young child is able to start a chore or assignment right after instructions are given. A high school student does not wait until the last minute to begin a project.

Planning/Prioritization: The ability to create a roadmap to reach a goal or to complete a task. It also involves being able to make decisions about what’s important to focus on and what’s not important. A young child, with coaching, can think of options to settle a peer conflict. A teenager can formulate a plan to get a job.

Organization: The ability to create and maintain systems to keep track of information or materials. A young child can, with a reminder, put toys in a designated place. An adolescent can organize and locate sports equipment.

Time Management: The capacity to estimate how much time one has, how to allocate it, and how to stay within time limits and deadlines. It also involves a sense that time is important. A young child can complete a short job within a time limit set by an adult. A high school student can establish a schedule to meet task deadlines.

Goal-Directed Persistence: The capacity to have a goal, follow through to the completion of the goal, and not be put off by or distracted by competing interests. A first grader can complete a job in order to get to recess. A teenager can earn and save money over time to buy something of importance.

Flexibility: The ability to revise plans in the face of obstacles, setbacks, new information or mistakes. It relates to an adaptability to changing conditions. A young child can adjust to a change in plans without major distress. A high school student can accept an alternative such as a different job when the first choice is not available.

Metacognition: The ability to stand back and take a birds-eye view of oneself in a situation. It is an ability to observe how you problem solve. It also includes self-monitoring and self-evaluative skills (e.g., asking yourself, “How am I doing? or How did I do?”). A young child can change behavior is response to feedback from an adult. A teenager can monitor and critique her performance and improve it by observing others who are more skilled.

Stress Tolerance: the ability to thrive in stressful situations and to cope with uncertainty, change, and performance demands.

Now that you have a deeper understanding of executive functioning skills, let’s review how stress impacts learning.

The stress response is evoked by a perceived physical threat that initiates the automatic survival reactions of fight, flight, or freeze. Even though physical threats are less prevalent for college students, psychological/social anxiety can still trigger the stress response. In these cases, the fight and flight responses that evolved to assist in a physical confrontation may instead manifest as anger and anxiety.

The less well-known freeze response occurs when a threat can neither be defeated or escaped. The freeze response happens when your body thinks that fight or flight does not have a chance. This often results in numbing out or dissociating from the here and now. Some neuroscientists believe that conditions such as anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) are directly connected to the stress response. In particular, anxiety may be due to chronic activation of the fight or flight system, and depression may be caused by a chronic activation of the freeze response.

Unfortunately, the brain does not distinguish between a physical threat or a psychological/social threat. As such, chronically anxious students are constantly triggering the stress response. The stress response impacts learning by shutting down brain activity in the prefrontal cortex - the portion of the brain responsible for critical thinking. At the same time, the limbic system, the lower area of the brain associated with emotion, begins to take over. Scientists contend that this response evolved to inhibit thinking and encourage action.

This is useful when the goal is to run from danger rather than overthink a situation, but it is not beneficial when the threat is an exam where thinking is paramount.

When the stress response is initiated, the hormones of adrenaline and cortisol are released. Adrenaline increases the heart rate and blood pressure. In a sedentary student, this results in an excess of nervous energy and anxiety that makes it difficult to calm down and mentally focus. Cortisol has a powerful impact on learning because it inhibits a student’s ability to integrate new information and retrieve old information. Said simply, it makes it difficult for a student to form and retrieve memories. In addition, cortisol causes cognitive inhibition – a state where students are unable to discern irrelevant information from goal-relevant information. Understanding this dynamic is important because students often interpret difficulty in learning as a lack of intelligence rather than as a natural physiological response to stress.

Overall, the stress response impairs executive functioning -- which is the set of mental abilities that include working memory, flexible thinking, and self-control. This explains why anxious students respond to academic troubles in ways that are not strategic and often counterproductive. Appropriate levels of stress can enhance learning by stimulating arousal, alertness, vigilance, and focused attention. However, the repeated, ongoing, pervasive stress common with college students has been shown to negatively affect learning and memory.

Many first-year students utilize the same strategies they used in high school to be successful, but they are shocked when these strategies fail them in college.

Whenever students experience failure, there is going to be an emotional response. This emotional response can negatively impact learning. Further, uncontrolled stress deskills students and deprives them of the executive functioning skills that they need to pull out of a downward spiral of stress-induced avoidance.

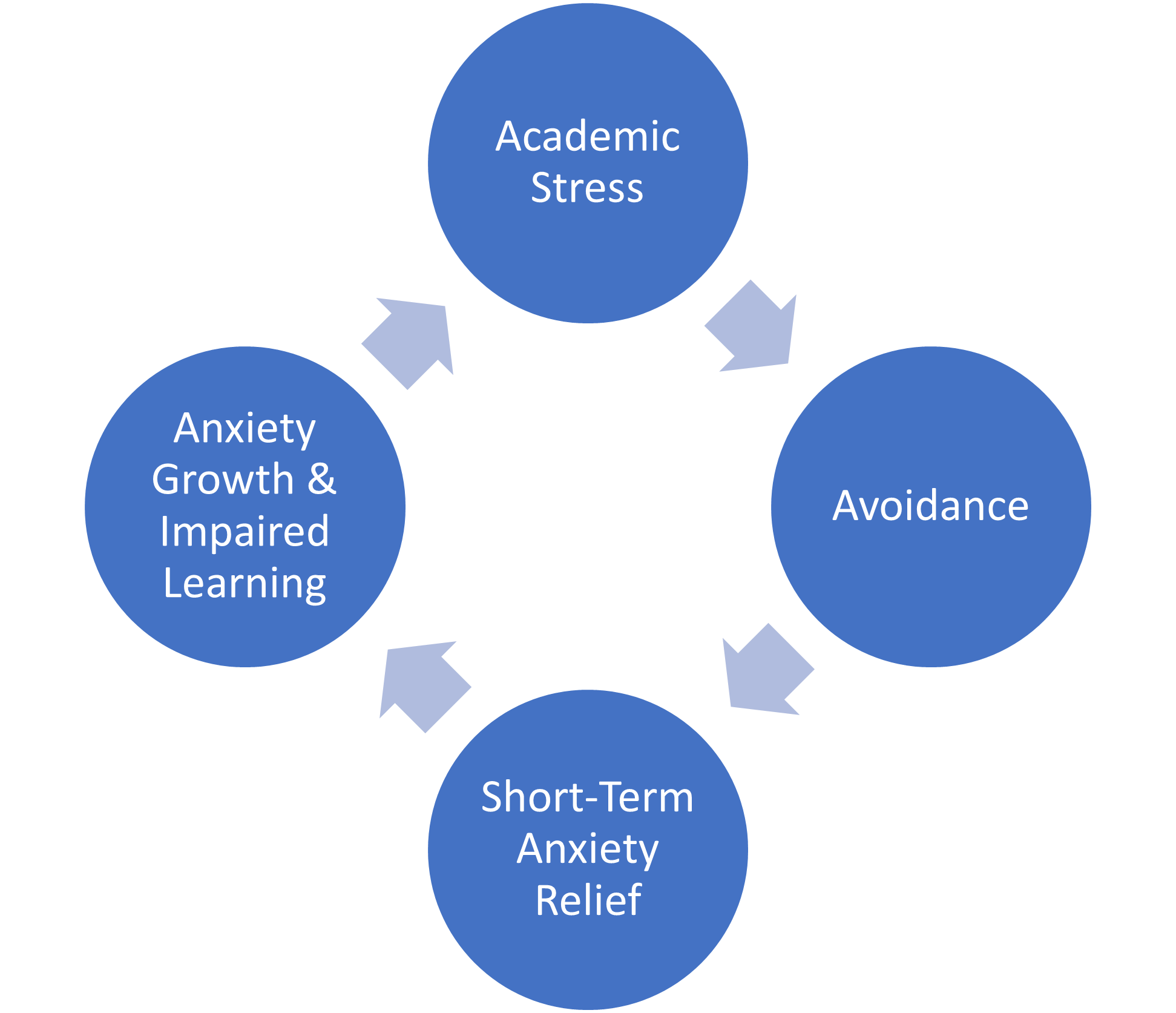

Students often feel a sense of psychological relief when engaging in avoidance. It feels good to put something off and not have to think about it. However, the small tasks that were put off soon begin to accumulate, which causes an even larger amount of anxiety and impaired learning due to the stress response. This leads to more avoidance and a viscous cycle where students fall further and further behind in their classes. When this happens, students risk falling into the Academic Avoidance Cycle.

When students chronically avoid their stressors, they fall so far behind that, even with a heroic effort, there may be no way for a student to recover academically. The result is often panicked late-night cramming and the collegiate tradition of making comparisons to see who is the most stressed out. Cramming students deprive themselves of sleep and other elements of a healthy lifestyle in a futile effort to complete large amounts of academic work in a short amount of time. This only worsens anxiety and is an ineffective learning strategy.

The mindset of a student significantly impacts their ability to succeed and determines how hard they work in the face of adversity. According to Carol Dweck, renowned psychologist and researcher, there are two different types of mindsets: growth and fixed.

Dweck’s research revealed that your mindset can have a remarkable impact on how you approach challenges and opportunities in your life. A fixed mindset student believes that their qualities are innate and unchangeable. Every situation a fixed mindset person encounters is one where they must prove their competence. This results in tremendous pressure to hide any perceived weakness for fear of judgment. This fear manifests in students who do not take risks and expend limited effort because they believe their deficiencies will reveal them to be permanently inadequate.

Since the fixed mindset students believe their situation can’t be changed, they freeze, stop exerting effort, and fall victim to a self-fulling prophecy of failure. Consequently, fixed mindset students easily lose interest or quit tasks that become too challenging. The addition of the creator and victim mindset to the more well-known growth versus fixed mindset adds the important element of student responsibility to the equation of student success.

The following video provides you with a deeper understanding of fixed vs. growth mindsets, creator vs. victim mindsets, and avoidance vs. approach behavior. Ultimately, this video encourages you to become aware of your mindsets and behavior so that you can overcome obstacles and reach your goals.

The creator mindset is a variation of Dweck’s growth mindset that focuses on the belief that personal choices create the outcomes and experiences of a student’s life. When a student has a creator mindset, they can see multiple options, discern among them wisely, and take effective action to achieve the life they want.

The creator mindset emphasizes an important psychological principle that is necessary for student success – the student must not only believe that change is possible but they must take personal responsibility to change their own behavior to achieve success. The following behaviors and beliefs indicate that you have adopted a creator mindset:

A victim mindset is another variation of Dweck’s fixed mindset. A student adopts a victim mindset when they believe the adversity they are experiencing is unfair. This results in students taking little or no responsibility for their predicament which, in turn, leads to decreased motivation to create positive change – learned helplessness. Ultimately, victimization allows students to forego the difficult work of self-reflection and improvement, which results in being entrenched in a passive/blaming state of mind that inhibits intellectual growth. You may be utilizing a victim mindset if you engage in the following behaviors or beliefs:

Research on self-pity further illuminates the victim mentality. Self-pity is the psychological state a student experiences when he/she/they believe they are the victim of unfortunate circumstances or events and are therefore deserving of condolence. Self-pity is insidious because the negative emotion it evokes can often lead to the reinforcement of the positive experience of receiving condolence without the painful work of transformation.

In short, a victim mindset is a coping behavior that gives students temporary psychological relief by allowing them to refuse any responsibility for their adverse situation. Ultimately, the focus on mindsets is a process of building mental strength, and much like building muscle, it is about taking intentional, continuous action to bolster mental fortitude in the face of resistance. It is not about using positive thinking to solve problems. For example, no amount of positive thinking will make the loss of a loved one better. Instead, it is about taking proactive action to deal with psychological pain and to persevere through hard times. In the same way that a physically fit person will heal faster from an injury, a person that has taken time to build mental resilience will heal faster when experiencing psychic trauma. Perseverance and increasing your capacity to do meaningful work is the goal of utilizing mindset theory in your academic career.

To disrupt the avoidance cycle, students should employ what are known as top-down and bottom-up strategies.

Top-down strategies use cognition to manage behavior. For example, teaching a student to manage their time, utilize specific study strategies, and track their behavior are all cognitive strategies. Bottom-up strategies focus on wellness and include prayer, meditation, yoga, exercise, and walking in nature, to name a few. When students fall behind academically, a common response is to grind, cram, and push themselves beyond their limits. These are short term strategies that will result in burn out and failure. By utilizing both top-down and bottom-up strategies, students can achieve the holistic balance needed to accomplish calm, focused, and consistent levels of work.

While you probably have been exposed to time management and wellness strategies in the past, this course gives you a system to seamlessly incorporate these strategies into your weekly study routine and provides you with holistic strategies as you adapt to new stressors in your life.

Uncontrolled stress saps students’ willpower and leads to an ever-worsening academic avoidance cycle. When this happens, it’s important to seek out help from trained professional staff. One way to determine whether you might need to talk with someone is to ask whether you are experiencing normal levels of challenge or if you are overwhelmed. A challenged student will often take action to address their stressors. In contrast, overwhelmed students cope by avoiding their stressors simply because they don’t know where to begin. The following table helps distinguish the difference between challenged and overwhelmed students.

| Challenged | Overwhelmed |

| Mental challenge is a cognitive state entered when a student is trying to master new content. | Overwhelmed is an emotional state entered when the volume of thoughts, feelings, tasks, and other stimuli push the student into cognitive overload. |

| Learning creates new neural pathways which can be experienced as frustration – growing pains. | Pre-frontal cortex shuts down and triggers the stress response – fight, flight, freeze (survival mode). |

| Learning is slow at the beginning as the brain develops neural pathways. This can cause anxiety but is quickly alleviated once things begin to “click”. | Being struck in survival mode makes it difficult for the student to complete simple tasks. The student often has trouble breaking down larger task into smaller steps. This results in passivity that is often accompanied by forgetfulness, mood swings, and noticeable anxiety. |

In addition to being overwhelmed into complete inaction, a pessimistic mindset is another sign that you should reach out to trained professional staff on campus. A pessimistic person believes that nothing can be done to improve a negative situation.

When optimistic students face academic adversity, they are more likely to take steps to change the situation because they believe the situation can be changed. When optimists encounter academic setbacks, they are more prone to believe that it is a temporary situation, and they will look for specific causes for the failure (e.g., “I didn’t study enough”). In contrast, pessimists are prone to believe that failure is a permanent condition and that their situation is pervasive or inescapable.

Your mindset has a significant impact on your academic performance, so if you find yourself thinking or believing that your current academic state is a permanent and inescapable situation, you should seek out campus resources, such as academic coaches, who can help you get moving toward your goals.

Module 2: Time Management

There is often a disconnect between the amount of time students think they will need to study and the amount of time they will actually need to study to be academically successful.

At Marquette, most students need between 20 – 30 hours of work per week to keep pace with their academic schedules, which is a substantial increase from high school, where students average less than 6 hours of study time a week! (It’s no wonder you might be feeling stressed out.)

Given this context, it makes sense that students have trouble adapting to the number of study hours required to excel academically, and it demonstrates the crucial need to help students build the willpower necessary for long hours of study.

In order to move from an anxious state of being that depletes cognitive resources to a calm mindset that optimizes willpower, improves learning, and helps you increase the time spent on your academic work, you need to increase the amount you study by habitualizing self-regulation behaviors. Habitualization is accomplished by following a workflow that establishes a routine. By consistently following the routine, you can build self-control, lower stress, and learn to approach your work in a calm and deliberate manner.

When you are feeling stressed and overwhelmed, it is important to have a structure and a way forward. You can do this by getting organized through the use of a master calendar, master to-do list, a weekly study schedule, and your Marquette Outlook Calendar. This process is based on David Allen’s Getting Things Done system of time management, which helps students organize the chaos and, most importantly, pushes them into action.

The master calendar is simply a monthly calendar. While many students will use digital calendars and calendars in large, paper organizers, students will often stop referring to them because with large organizers students tend to focus on the day-to-day section, and with digital calendars, it is hard to easily review a month at a time.

However, the implementation of a simple paper calendar using Microsoft word for each month of the semester assists students in developing the executive functioning skill of planning. Students must plan backwards from a due date and create a roadmap to reach each goal and complete each task. It also teaches students to make decisions about what is and is not important to focus on.

By using an easy-to-review calendar of the semester, you can quickly review the semester at-a-glance and clearly see the work that you need to accomplish.

When filling out the master calendar, review your syllabi and put everything that is worth points in the calendar – this means that every single assignment or test for the entire semester should be placed throughout the calendar.

Then, put the percentage that each assignment or test is worth on the calendar. For example, “Test One (25%). The purpose of putting the percentage next to the assignment is to encourage you to think strategically.

If you have numerous things due during the same week, you should be able to plan backwards to reserve enough time to complete all of your work.

Even so, the best of students will get caught in situations where they do not have enough time to do all their work, or perhaps, they are dealing with personal issues that are sapping their mental reserves. By looking at the percentages next to their assignments, they will know strategically where they should be spending their limited time and mental energy. For example, if a student has a psychology exam that is worth 10% of the grade and a calculus exam that is worth 25% of their grade, they should make sure that they are committing more time toward calculus.

While the goal is to learn deeply, strategically you may need to chase points and get the most return on the investment of your study time. This also helps guard against the emotional urges to study the topic you enjoy while putting off the subject that is causing stress. For example, you may enjoy psychology and spend the bulk of your time studying psychology instead of calculus. If you ace your psychology exam but get a lower grade in calculus, this was not a strategic use of your time because the calculus exam was worth more points toward the final grade.

While putting assignments on a calendar is basic, many students don’t do this important step. In college, the main stressor is academics, so it is not uncommon for a student to avoid their calendar until they end up in a situation where they are caught off guard and must cram to make up for lost study time.

Regardless of the organization system you choose, you should look at the work you must complete in the semester daily. If out of sight is out of mind, you should have a daily habit of looking at the entirety of the academic work for the semester.

If you are standing in the ocean, you need to face the wave coming at you or it will knock you off your feet.

There are many sophisticated ways to create to-do lists, but you should start with the basics. Ideally, you should have a master to-do list that is easy to access and that you trust to capture your thoughts and to-dos. For example, using an app on your phone is a reliable option because it usually ensures the list won’t get lost, and it avoids the confusion of writing to-dos in multiple locations. It is even better if you can add to-dos with a digital assistant that can capture voice commands. This allows you to capture thoughts and tasks while you are on the move. However, a simple paper list will do if it is the only list, and it is kept in an easy to access place.

The to-do list helps you avoid cognitive overload. If you can effectively capture thoughts and to-dos in a system you trust, you do not have to waste the mental energy of trying to remember tasks. The goal is to get tasks out of your head and into a trusted workflow system. The master to-do list helps declutter your mind so your working memory can be fully engaged in completing tasks.

A weekly study schedule serves the dual purpose of spreading study sessions throughout the week while helping you develop good habits by consistently sticking to a routine. By sticking to a routine, you will gradually increase your self-control and willpower (the ability to get things done).

Routines serve to drive and reinforce motivation, and in the process, they help you develop procedural memory. Procedural memory refers to a type of long-term memory that mediates the habits you use daily without consciously realizing it.

This autopilot mode involves knowing how to do something so well that you don’t stop to consider each stage of the process – it happens seamlessly and effortlessly. Procedural memory is important because once you become familiar with a routine, the process becomes automatic so that working memory is freed up and can instead be used to focus on task completion.

In addition to freeing up your working memory, the weekly schedule helps you develop the executive functioning skills of planning, problem solving, and inhibitory control. The weekly schedule also assists in metacognition because it provides you with immediate feedback as to whether you were able to stick to your study plan. Over time, you will learn to recognize if you are keeping pace with your academics or falling behind.

Through intentional planning you can build routines that help you limit stress. The idea is that you are consistently busy and working in a calm and deliberate manner rather than moving back and forth between stress-filled cramming and periods of no productivity due to burn out – a “put out the fire” method of time management often utilized by overwhelmed students.

If used properly, the weekly schedule is a powerful executive functioning development tool that can help you avoid burnout and successfully navigate your personal and academic commitments.

Your weekly study schedule blocks off time to work, but these blocked off times won’t have assigned tasks until you conduct a weekly review process. During your weekly review, you will look at your master calendar, master to-do list, and your weekly study schedule. Your master calendar and master to-do list will show what work is coming your way and which work you should prioritize.

You will look through your upcoming week, review all your meetings, classes, and blocked off study time. Once you have a comprehensive idea of what needs to be accomplished in the upcoming week, you will assign specific tasks from the master to-do list to your blocks of study time on your weekly schedule.

It is easier to knock items off your to-do list if you only must accomplish one or two things in a work session. The tasks should be doable in the assigned time frame. For example, a student may have set aside an hour to work on their English paper with a to-do listed as – find three articles on “x.” This is more specific and goal-oriented than a “do research” to-do. During a non-study hour, the student to-dos may be – text friend about dinner tonight, email boss about work availability. It is common for to-do items to be comprised of a mix of academic, social, and work items because life can’t always be perfectly compartmentalized. Although, you should try to put one hundred percent focus on your academics when they are in an assigned study time.

While thinking ahead about a week’s activities and to-dos is relatively simple, there is a surprising amount of psychology involved in this process. However, by utilizing the weekly review you can be strategic and create a calm workflow that is adapted to each week’s unique challenges.

As you conduct your weekly review and build your more-specific weekly study schedule, consider asking yourself the following questions:

Your answers to these questions should guide your weekly study schedule and will allow you to move beyond time management and recognize that energy management is the more productive endeavor in navigating a modern life that doesn’t conform to the boundaries of traditional work hours and personal time.

Tip: Many students will do the work they enjoy most first while putting off the work they dread last. As a result, they end up doing their hardest work when they are the most depleted. This only reinforces that they don’t like a particular class or that they are not good at a particular subject. Instead, try to do your hardest work during the hours when you are at your best – your prime-time hours. It is a small adjustment that often has a significant impact.

One of the most efficient and effective ways to manage your weekly study schedule is to utilize your Outlook Calendar, which all students have access to through their Marquette Email.

Module 3: Study Strategies

In terms of study strategies, we recommend the CORE system. The Downing CORE Learning System utilizes four stages of studying – Collect, Organize, Rehearse, Evaluate. The CORE learning system is particularly important as it gives an overall structure for your learning. By following the CORE Learning System, you will learn how to utilize elaborative study strategies and memory retrieval.

There are several common types of learning strategies – rehearsal strategies, elaboration learning strategies, and organization strategies. Rehearsal strategies use repetitive exposure to what the student is trying to learn. Examples of this strategy are flash cards, quizlet, and rereading notes. These passive rehearsal strategies utilize mindless rote repetition that usually does not result in meaningful long-term learning.

In contrast, elaboration learning strategies require students to use cognitive processes where the student adds to or modifies the material they are trying to learn. Examples of this strategy include paraphrasing, summarizing, creating analogies, using compare and-contrast strategies, applying the material one is learning, creating/answering test questions, and teaching someone else.

Lastly, organization strategies focus on reorganizing material into a graphic organizer. Examples of this strategy are creating outlines, cause-effect diagrams, mind maps, and relationship diagrams – these strategies are also useful and come into play after you’ve collected the essential information you need to study.

Now that we’ve discussed the basics of the CORE learning system, let’s break it down further.

The C stands for collect. This simple but important step focuses on teaching students to effectively collect information through note taking, reading, and course materials. The goal is to capture questions, clarify information, and ensure that you are collecting the essential information from the proper resources.

Note-taking and reading comprehension are essential skills that will help you successfully collect the right information.

Cornell Notes help to create a dialogue between the notes your professor gives you in class and your own thought process. All you need to do is simply divide the page in your notebook to include a space for your lecture notes, your questions, and a summary. When you write your summary, simply write everything you remember from class. It doesn’t need to be perfect! The video below provides a visual guide.

The commonality between note taking and reading is identifying essential information, asking good questions, summarizing what you learned, identifying what you don’t know, and finding the answers for knowledge gaps. This is active learning!

Tip: It is important to write down questions before you forget them, and to take time after class to write a summary of what you learned. In academic coaching, we refer to this as doing a “brain dump.” Writing down questions and then later finding the answers, as well as summarizing what you remember from your lecture, helps you shift from passive learning to active learning -- where you are hunting for answers and identifying what you don’t know.

This ensures you are adding information to the lecture. Most students learn in high school by copying down exactly what the teacher said and then rereading the notes before an exam. Consequently, when students arrive at college, they just copy down exactly what is on the professor’s PowerPoint and expect that rereading their notes will prepare them for the exam. But students often don’t understand that the bullets on the PowerPoint are the professor’s way of saying “these are things you should study on your own.” The PowerPoint points to what is important.

The O stands for organize. Students organize their materials by rewriting their notes. While their notes may look prettier, this is a superficial practice. You need to go deeper and actively manipulate the information rather than just rereading the material.

Once again, the goal is to switch from passive to active learning. To make this switch, students should learn to create study guides where they identify key concepts, organize them into small easy to memorize chunks, put the concepts in their own words, create their own examples, make drawings, and come up with mnemonics, acronyms and/or other memory assisting techniques.

When students organize information into a study guide, they are also doing the hard work of organizing the information in their brain. This makes it easier to connect new information to prior knowledge a student has already mastered.

One of the most effective ways to learn is to connect new information to prior information. When students are learning new and unfamiliar material, it is often a collection of facts that are a jumble in the student’s mind. If the student does not impose order on this knowledge, when new information comes in, it can become lost in the jumble rather than being placed in a logical, easy-to-recall place. It is like buying a coffee mug at the store. When you bring it home, you put it with the other coffee mugs in your house, so when you want to use this new mug, it is easy for you to find. However, if you don’t have an organizational system and you randomly place this new coffee mug somewhere in your house, you are less likely to be able to find my new mug when you want it.

Even if students use a provided study guide, it is not as effective because the student did not do the hard work of organizing.

When you study someone else’s study guide, you run the risk of simply rereading material which is an ineffective rehearsal strategy. If the professor provides a study guide, consider using it as a starting point for your own study guide. By doing this, you actively manipulate and organize information in way that makes sense to your unique brain. By building your own study guide, you break habits of passivity and embrace active learning.

Since each semester is only 16 weeks long, learning to memorize and recall information quickly is a vital collegiate skill. By using an outline-based study guide, students can create a cognitive map where they can hang small chunks of about four essential pieces of information that they need to remember. The outline method allows them to nest these essential pieces of information (visualize a Russian nesting doll), which is important because it shows relationship between concepts. The graphic nature of the linear outline taps into visual intelligence by allowing students to “see” their knowledge organized in a cognitive map while chunking and nesting information taps into spatial intelligence by helping students see how information is connected to each other.

In this sense, a good study guide serves as a memory palace that helps students organize and recall the jumble of information they are trying to master. When students construct their own study guides, they are challenged to think deeply about what information is essential and how to organize the information into coherent chunks of interrelated information. The study guide allows students to “see” their knowledge which makes it easier to synthesize and apply ideas.

The memory palace is a mnemonic device that provides a mental retrieval map. It is a systematic memory tactic that dates back to ancient Greece where orators used it to remember aspects of long speeches. The memory palace beautifully demonstrates the importance of creating a framework or infrastructure to hang new knowledge on.

The R stands for rehearse in Downing’s original CORE Learning System, but for the purposes of this course, it has been changed to recall or retrieval practice as a way for you to learn more about neuroplasticity and the critical role of memory retrieval.

Once you have built your study guide, it is time to use memory retrieval to efficiently move knowledge into long-term memory. Unfortunately, most students don’t use memory retrieval to study, and instead, study through repetition, which engages short-term memory.

When students study through repetition, they make loose neural connections, but since they did not do the work of retrieving this information from memory, they are not making the dense neural connections that move knowledge from short-term memory to long-term memory.

If you find you can explain what your notes looked like, but you can’t recall the information or you take an exam and can remember that the answer you are looking for was written in red ink, in the upper left-hand corner of your notebook, but you just can’t retrieve the information, this a tell-tale sign you are using repetition studying – studying with the answer in front of you.

While simple rehearsal strategies, like repetition, will create neural networks (i.e. long-term memory) the process is slow.

Neuroplasticity is the ability of neural networks in the brain to change through reorganization. This change happens through a process of repeated firing of a certain sequence of neurons. Simply stated, neurons that fire together wire together (Hebb’s Law!).

Since college students are racing against a fast-paced semester, they need to supercharge their memory formation by recalling information from memory without their study materials in front of them. Memory retrieval is more effective than simple repetition because it forces students to practice with information, and while recalling, students will naturally organize and paraphrase information in a way that makes sense to them.

Moving Information to Long Term Memory

Retrieval practice is not simply memorizing. It is about practicing with material and reconstructing knowledge. Students that utilize retrieval practice can solve problems instead of memorizing solutions, they are able to make connections and provide rich explanations rather than just repeating facts. Every time you retrieve a memory, it becomes deeper, more robust, and easier to retrieve.

Each time you practice memory retrieval, you are testing yourself. In other words, you are studying in the exact same way you will be tested.

A Note on Time Management:

When you understand that learning is a physiological process that literally changes the structure of your brain, it is easier to understand that memory retrieval learning takes more time. For example, when you work out, the exercise creates small micro-tears in your muscles. By resting, you give your body time to repair the micro-tears which creates increased muscle tone. Since we can feel the soreness of micotears, most people inherently understand the need to rest after strenuous physical exertion. Our brain is a complex physical organ that also needs time to recover and build neural networks after a strenuous mental work out. When students grasp this concept, it becomes obvious that you can’t physically change your brain in a cramming session. You need to learn to space out your “mental workouts,” so your brain has time to build new neural networks.

Learning has not occurred unless knowledge is encoded into long-term memory. So, students must break the high school habit of studying a few days before an exam and learn that if they have three weeks between exams that they must use all this time to utilize the CORE learning system. Understanding neuroplasticity is key to understanding the importance of distributing learning throughout the week.

There is no better practice of memory retrieval than the Feynman Technique. The Feynman Technique is a four-step learning method developed by 1965 Nobel Prize in Physics winner Richard P. Feynman. The Feynman technique promotes learning through teaching. The more you teach a subject, the better you grasp it. The more you grasp it, the better you are at simplifying information and teaching it in a way that both yourself and others will comprehend.

The Feynman Technique exemplifies the concept of metacognition – thinking about thinking. The goal of this cyclic process is to use memory retrieval, self-monitor one’s own understanding, and continuously interact with content until you can identify the subject’s essential parts and explain how those parts interact.

It moves past the regurgitation of facts to the understanding of the why and how. When you understand the core principle behind whatever content you are learning, you can move beyond remembering and understanding to the higher-order thinking that is valued in college – apply, analyze, evaluate, create.

When you are done creating your study materials, consider using the Feynman Technique to practice with and master the content you are learning.

Teaching and recalling information without the answer in front of you are both examples of the E in CORE. The E stands for evaluate. Students must be able to effectively evaluate what they know (metacognition). If a concept has five steps and you are only able to recall three, you now know you need to focus on the two missed steps. If you take a practice exam and fail one section of the exam, you now know which area you should focus on. This practice is also beneficial because it can help time-strapped students know what information they should prioritize in their studying.

Another important piece of evaluation is reviewing an exam. It’s common to feel so much emotional pain from an exam that you refuse to review it. However, reviewing an exam is an excellent way to reevaluate learning strategies. Be sure to review any question you missed. Why did you miss it? Was it a simple mistake? If so, you may need to spend some time covering basic test taking strategies. Did you not know the answer? If so, go back to your study guide and look for the answer. Was the answer in your study guide? If so, you were not spending enough time doing memory retrieval practice. Was the answer not in your study guide? If so, you need to examine whether you are collecting the right materials.

A test is the biggest clue as to what a particular professor finds important, where this professor pulls questions from, and the general format of future exams. It is essential for students to evaluate and learn from their performance on exams.

Module 4: Resources

This course was designed to help you learn more about the academic strategies you can use to be successful during your time at Marquette. However, you must embrace the concept that rest, recovery, and reflection are essential to live a sustainably successful life – and, that no matter how much you plan, life will happen.

If you find yourself needing or wanting additional assistance with time management and study strategies, please reach out to the Academic Resource Center. We are located in Coughlin Hall, 125.

To set up an appointment with an academic coach, please email academiccoaching@marquette.edu or schedule an appointment here.

Works Cited

Anderson, L. W., Krathwohl, D. R., Airasian, P. W., Cruikshank, K. A., Mayer, R. E. Pintrich, P. R., Raths, J., & Wittrock, M. C. (2001). A taxonomy for learning, teaching, assessing: a revision of Bloom’s taxonomy of educational objectives. New York Longman.

Apostolopoulos, N. (2004). Microstretching®: a new recovery regeneration technique. New Studies in Athletics, 19(4), 47-56.

Baumeister, R. F., Vohs, K. D., & Tice, D. M. (2007). The strength model of self-control. Current directions in psychological science, 16(6), 351-355.

Bracha, H. S. (2004). Freeze, flight, fight, fright, faint: Adaptationist perspectives on the acute stress response spectrum. CNS spectrums, 9(9), 679-685.

Chase, M. A. (2019). Stemming the tide of work-related stress: it’s not rocket science, it’s neuroscience. Development and Learning in Organizations: An International Journal.

Dawson, P., & Guare, R. (2009). Executive skills: The hidden curriculum. Principal Leadership, 9(7), 10-14.

de Kloet, E. R., de Kloet, S. F., de Kloet, C. S., & de Kloet, A. D. (2019). Top‐down and bottom‐ up control of stress‐coping. Journal of neuroendocrinology, 31(3), e12675.

Downing, S. (2017). On course: Strategies for creating success in college and in life. Nelson Education.

Dweck, C. S. (2006). Mindset: The new psychology of success. Random House.

Eichenbaum, H. (2010). Memory systems. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Cognitive Science, 1(4), 478-490.

Handwerk, B. (2017, March 13). Neuroscientists Unlock the Secrets of Memory Champions. Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved January 2, 2023, from https://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/why-you-can-train-your-brainmemory-champion-still-forget-your-car-keys-180962496/

Hebb, D. O. (1949). The organization of behavior: a neuropsychological theory. J. Wiley; Chapman & Hall.

Hockey, B., & Hockey, R. (2013). The psychology of fatigue: Work, effort and control. Cambridge University Press.

Honos-Webb, L. (2018). Brain Hacks: Life changing strategies to improve executive functioning. Emeryville, CA: Althea Press.

Karpicke, J. D. (2012). Retrieval based learning: Active retrieval promotes meaningful learning. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 21(3), 157-163.

Kirschner, P. A., Sweller, J., & Clark, R. E. (2006). Why minimal guidance during instruction does not work: An analysis of the failure of constructivist, discovery, problem-based, experiential, and inquiry-based teaching. Educational psychologist, 41(2), 75-86.

McGonigal, K. (2016). The upside of stress: Why stress is good for you, and how to get good at it. Penguin.

Pipes, T. (2017, July 21). Learning From the Feynman Technique. Medium.com. Retrieved January 2, 23, from https://medium.com/taking-note/learning-from-the-feynmantechnique-5373014ad230

Roelofs, K. (2017). Freeze for action: neurobiological mechanisms in animal and human freezing. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 372(1718), 20160206.

Sagi, Y., Tavor, I., Hofstetter, S., Tzur-Moryosef, S., Blumenfeld-Katzir, T., & Assaf, Y. (2012). Learning in the fast lane: new insights into neuroplasticity. Neuron, 73(6), 1195-1203.

Seligman, M. E. (2006). Learned optimism: How to change your mind and your life. Vintage.

Seligman, M. E. (2012). Flourish: A visionary new understanding of happiness and well-being. Simon and Schuster.

Shields, G. S., Bonner, J. C., & Moons, W. G. (2015). Does cortisol influence core executive functions? A meta-analysis of acute cortisol administration effects on working memory, inhibition, and set-shifting. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 58, 91-103.

Stull, A. T., & Mayer, R. E. (2007). Learning by doing versus learning by viewing: Three experimental comparisons of learner-generated versus author-provided graphic organizers. Journal of educational psychology, 99(4), 808.

Syme, K. L., & Hagen, E. H. (2020). Mental health is biological health: Why tackling “diseases of the mind” is an imperative for biological anthropology in the 21st century. American journal of physical anthropology, 171, 87-117.

Weinstein, C. E., Acee, T. W., & Jung, J. (2011). Self‐regulation and learning strategies. New directions for teaching and learning, 2011(126), 45-53.

Report an accessibility problem

To report another problem, please contact academiccoaching@marquette.edu.

Lemonis Center for Student Success

1415 W. Wisconsin Ave.

Milwaukee, WI 53233

Phone: (414) 288-4252

Privacy Policy Legal Disclaimer Non-Discrimination Policy Accessible Technology

© 2025 Marquette University