GUIDE TO CATHOLIC RECORDS ABOUT NATIVE AMERICANS IN THE U.S.

Volume 5: Help Pages

Preface2

In 2004, the National Historical Publications and Records Commission (NHPRC) provided Marquette University, Raynor Memorial Libraries, with $83,000 to conduct a two-year survey of Catholic-related records about American Indians in the United States, in order to produce a Guide to the archives in fourteen Western States (Alaska, Arizona, California, Colorado, Hawaii, Idaho, Montana, New Mexico, Nevada, Oregon, Texas, Utah, Washington, and Wyoming). This Guide was meant to reproduce the functions of an earlier Midwest Guide—originally produced in the 1980s by Philip C. Bantin and Mark G. Thiel, and revised online by Thiel in recent years. The earlier Guide (1984) surveyed 823 institutions in twelve Midwestern states (Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Michigan, Minnesota, Missouri, Nebraska, North Dakota, Oklahoma, South Dakota, Wisconsin), and included descriptions of 277 Catholic missionary and educational institutions devoted to Indians in the U.S. The 2003-4, web-based revision added seventeen repositories to the Midwest Guide, and included several new features, including Library of Congress subject headings and a glossary of Catholic and Native terms.

The initial Midwest Guide grew out of the ambition of the Marquette Archives personnel to locate repositories of primary sources regarding Catholic mission and school efforts among American Indians throughout the U.S. This project recognized the growing scholarly interest in American Indian history and culture, and the dearth of systematic information available to scholars searching for Indian data. A 1979 Preliminary Guide to Major Repositories of Catholic Indian Mission Records served as a first draft; however, the task transcended the scope of the Preliminary Guide. There were far too many repositories, and their holdings were too vast, and also too disordered, for such a faint beacon to show the way.

With funds from the National Endowment for the Humanities, Marquette Archives produced its Midwest Guide, focusing on repositories at Catholic missions and schools; at religious institutions, like dioceses and congregations; at non-Catholic libraries, like those organized by historical societies and universities; and at facilities conducted by Indian tribes.

The resulting Midwest Guide provided entries, state by state, institution by institution, pointing the way to the leading repositories. The Guide included a chronological account of each relevant Catholic diocese, school, mission, order, etc., as documented in The Official Catholic Directory (1817-) and buttressed by Marquette's holdings of the Bureau of Catholic Indian Mission (BCIM) Records. The Marquette staff defined the types of Catholic institutional outreach to Indians (parishes, mission stations, chapels, churches, etc.), and provided an index of individuals and organizations. Finally, a bibliography of reference works, histories, archival guides, genealogies, Indian languages, and other special study resources were included in order to help researchers find their way.

The 1984 Guide was a treasure trove to an historian like myself. The Midwest Guide pinpointed Catholic agencies involved in Indian work, the many dozens of tribes affected by Catholicism, and their inclusive documentary dates. It had the advisory input of esteemed scholars such as Rev. Francis Paul Prucha, S.J., Professor of History at Marquette University, and Herbert Hoover, Professor of History at the University of South Dakota, and it carried the imprint of dedicated archivists. In the late 1980s I set out to write a history of American Indian Catholicism, primarily within the area now defined by the United States, from earliest contacts to the present day. After more than a decade of research I produced three volumes (American Indian Catholics, 1996, 1997, 1999), published by the University of Notre Dame Press. At the outset, and throughout my research, the 1984 Guide helped me locate sources. The entries told me where I could locate correspondence, financial accounts, school files and registrars, bureaucratic reports, memos, agendas, the minutes of meetings, photographs, baptismal and other sacramental records, diaries, news clippings, land titles and deeds, manuscript essays, memoirs, ledger books, census records, and various types of publications, like newsletters and circulars. There was a variety of repositories, including federal archives, Catholic missions, congregations of priests and sisters, university libraries, parishes, museums, dioceses, abbeys, historical societies—replete with contact information.

I used the Guide to good effort, e.g., to peruse all the holdings at the Archives of the University of Notre Dame (see pp. 12-17 of the Guide). St. Dominic's Church in Holton, Kansas, and the Archdiocese of Kansas City in Kansas (see pp. 32-34 of the Guide) held a good deal of information about the development of Potawatomi Indian Catholicism, which I was able to obtain, with the Guide in hand.

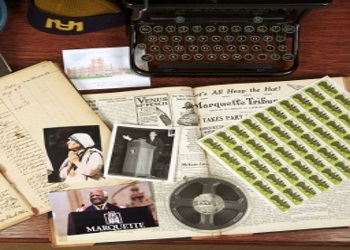

Perhaps the richest Midwest resource, I found, was Marquette's own Department of Special Collections and University Archives (see pp. 383-390 in the Guide), with its voluminous holdings (268 cubic feet, 48 rolls of microfilm, 212 reel to reel audio tapes), including the prodigious records of the Bureau of Catholic Indians Missions (BCIM), 1854-1976; the collection, 1852-1978, regarding Holy Rosary Mission among the Oglala Lakota Indians at Pine Ridge Reservation, South Dakota; the St. Francis Records among the Brulé Lakota Indians on the Rosebud Reservation in South Dakota, 1888 1890, and so forth. I mined these thoroughly, and advised a former student, Ross Enochs, to concentrate his dissertation research at Marquette, where he wrote his excellent book, The Jesuit Mission to the Lakota Sioux. Pastoral Theology and Ministry, 1886-1945, published by Sheed & Ward in 1996. Many other scholars like Marie Therese Archambault, Joëlle R. Rostkowski, Raymond A. Bucko, and Michael F. Steltenkamp were informed by the 1984 Guide and their published works on American Indians' relations to Catholicism demonstrated the worth of the Guide, and the Marquette archives in particular.

In all honesty, however, as I look over the wealth of materials now in the Midwest Guide, I can only regret all the sites I neglected. Just one example: My personal association with the Catholic Ojibwa peace activist and liturgist, Larry Cloud Morgan, would surely have been enhanced if I had gone through the archive at St. Joseph's Church in Ball Club, Minnesota (see pp. 91-92 in the Guide), when I visited him at his home there on the reservation.

The Guide was meant not only for scholars. The updated Midwest Guide noted how Indian communities employed the Guide for genealogical purposes, to help prove citizenship or Native ancestry, and for the preservation or restoration of cultural heritage. Here were documents that could demonstrate the past and recent actions of the Church, government, and tribes, and the Guide made it possible for individuals and communities to unearth those testimonies, waiting to be discovered.

Marquette did not cease its energy in gathering archival materials from small repositories and in organizing their own holdings—and the updated Guide let the archivists at these places know how to make their materials available to scholars and the general public. We can see—by virtue of a sample Marquette document (Schedu~1.doc) concerning "RECORD RETENTION & DISPOSITION" at Red Cloud Indian School, St. Francis Mission, how Marquette advised Catholic archivists in the hinterland. Similar documents exist for Buechel Museum/Heritage Center, KINI Radio Station. They explain what gets shredded, after how many years, what gets kept, what goes to Marquette Archives, and what gets placed onto microfilm, and deserves digital scanning. These documents show Marquette's relationship to Catholic repositories and the overall Catholic policies of retention, disposal, and transfer of archives.

Not content with the Midwest repositories, Marquette University Libraries' website produced in 2003 a small, preliminary Guide to Catholic-Related Native American Records in Eastern Repositories, based on the Midwest model: including, e.g., microfilm copies of the BCIM archives at Catholic University of America and the National Archives and Records Administration in Washington, D.C. (here especially one can see the interrelationship between Catholic religious efforts and more political and economic dimensions of Indian life, e.g., land management, trade, war, and church-state matters), and several other archive repositories. Some of the Eastern archives can give us a glimpse into the workings of the Catholic hierarchy regarding Indian schools and missions and U.S. Indian policy matters. For instance, the Archdiocese of Baltimore Office of the Chancellor contains the papers of Archbishop James Roosevelt Bayley, who helped create the BCIM, and James Cardinal Gibbons and Archbishop Michael J. Curley, both of whom served on the BCIM board. The papers of the great benefactor of Catholic missions, St. Katharine Drexel, are housed in the repository of the Sisters of the Blessed Sacrament for Indians and Colored People, in Bensalem, Pennsylvania. The same archive, of course, can open the doors of information regarding this order of sisters, long dedicated to the evangelization and education of Native Americans.

Marquette has continued to gather materials, state by state, throughout the Eastern region: Alabama, Florida (the P.K. Yonge Library of Florida History, University of Florida in Gainesville has holdings regarding Catholic evangelization among the Apalachee, Guale and Timucua Indians, from the sixteenth to the nineteenth century, connected by microfilm to other resources in Cuba and Spain), Kentucky, Louisiana (Marquette would do well to locate the Historical Research Center, Diocese of Houma-Thibodaux, in Thibodaux, which has valuable holdings regarding the Catholic Houma Indians), Maine (the Diocese of Portland Archives have materials regarding the Catholic Penobscot and Passamaquoddy. Marquette says that these materials are "unknown," but I have gone through them and they are worth a visit), Massachusetts, Mississippi, New Jersey, New York (Marquette should note the Diocese of Ogdensburg Archives, regarding the Catholic Mohawks at Akwesasne), Ohio, Vermont, Virginia, and so forth. There is much to locate in this region of the U.S.

An additional online Guide to Catholic-Related Native American Records in Foreign Repositories refers to the Leopoldine Society Archives in Vienna, which can inform scholars of the missionary agency that sponsored the nineteenth-century efforts of the famous cleric, Reverend Frederic I. Baraga and his colleagues, who established Catholicism among Indians in the Old Northwest and across America. Marquette has continued to search in Europe, e.g., in Belgium, at the Diocese of Louvain, at Bibliothèques de l'Université Catholique, regarding Reverend Peter F. Hylebos, 1879-1919, who evangelized among the Lummi, Nisqually and Puyallup in Washington State. Or in Germany, the Ludwigs-Verein missionary foundation, which launched Indian missions from Munich in the 1830s, or the Sisters of St. Francis of Penance and Christian Charity, who worked so long in South Dakota among the Sioux. In France, the Jesuit Lyons Province Archives has plenty of material regarding the Iroquois, Ojibwa, Ottawa, Wyandot, Choctaw, Tunica, etc. In Switzerland there are materials from the Benedictines in the Dakotas. In the Turin Province archives in Italy one can find Jesuit correspondence from the nineteenth and twentieth centuries regarding Alaskan missions. No doubt these findings will continue to grow on the Marquette website.

The Marquette staff has continued to stretch its geography of archival interest: to Canada, the Caribbean, and South America. Marquette has already begun to survey all the Canadian provinces and the National Archives in Ottawa. The Archdiocese of Edmonton, Alberta "is believed to include 19th century U.S. Native Catholic records from the Oblates of Mary Immaculate." This would be a valuable resource, were it found to exist, matching those in Manitoba at the Manitoba Province Archives of the Oblates of Mary Immaculate. The Archdiocese de Sainte-Boniface contains important data regarding the Métis communities that began in the Red River area of North Dakota in the 1800s. And of course, the Hudson Bay Company Archives in the Provincial Archives of Manitoba are invaluable, although perhaps only indirectly bearing on Catholic development. In Ontario, there are archives regarding the Ojibwas in Minnesota. Quebec has documentation concerning Mohawks, Ojibwas, Ottawas, both in Canada and the U.S. Still, in most Canadian locales there is still plenty of work to do to find repositories of Catholic-Indian import.

South of the U.S. border, Mexico is very important for leads into the Catholic history of the American Southwest. The archdioceses of Guadalajara, Durango, Hermosillo, Monterey, México, Puebla—all were planning centers for missionary work throughout northwestern New Spain, including what is now Texas, Arizona, New Mexico, California, and parts of Colorado and Utah. Their holdings are still largely "unknown" to Marquette's archivists, but crucial for sure. Peru was also a station for evangelization in the coastal U.S. area from Florida to Virginia. Cuba should also have considerable Catholic archival materials from the colonial epoch, although they are largely unmined by U.S. scholars. Puerto Rico's untapped potential is also intriguing, not to mention the Virgin Islands, where Taino Indian records exist.

Even in Asia, India might have some materials relevant to Native American Catholicism, as suggested in the Marquette website. Marquette also has helpful lists available online: a Glossary of Native Terms and a Glossary of Catholic Terms, a Master List of Catholic Groups from Augustinians to Xavierians, a Master List of Native Groups in the United States and beyond from Abenaki to Zuni, and a list of notable Non-Catholic Church Repositories, plus an A-Z Index and Bibliography, posted in 2003 as appendices.

For all of these things available on the user-friendly Marquette website, the 2004-20006 search for repositories in fourteen Western States constituted an expanded ambition—potentially a fulfillment and a complement to the Midwest Guide. Mark G. Thiel, Project Director, has engaged in outreach, onsite visits, and record-keeping, and he has produced a new Western Guide. He says that he has been "well received by virtually all archivists and record keepers," who have been "helpful and enthusiastic" regarding this NHPR funded project.

We see Thiel's initial contact survey—in which he asks archivists if their institution keeps "Catholic records about Native Americans or historical documentation about Native American relationships with the Catholic Church," and if so, what are the types of archival records (correspondence, statistics, diaries, news clippings, photographs, interview recordings, etc.) in their repositories, what is their volume, their condition, and so forth.

What were Marquette's project goals? To survey, identify, describe, and perhaps preserve "Catholic Church-related records about native peoples in the United States" in repositories of fourteen Western states. Here were centuries of documentation, waiting to be catalogued; sources "essential for . . . understanding the past and present life, culture, and relationships of Native American individuals and communities . . . ." Thiel also wanted to see which archives were "'at-risk,'" and try to save them. The aim was to produce a substantial Western Guide to these repositories, and then merge with the online index to Midwest Guide, which would serve as a "model."

What does this new Western Guide provide us regarding archives and their sources? It uses the same format as the earlier Midwest Guide: in regard to institutions, contact information, available facilities, and descriptions of the holdings: their volume, their genres (photos, correspondence, artifacts, maps, audiocassettes, videocassettes, diaries, etc.), their temporal and geographical scope, their subjects—the tribes involved and the Catholic agencies; particular persons of prominence.

There are 537 entries for the Western Guide (as compared to 277 in the 1984 Midwest Guide), well more than the goal of 280 set for this Guide. The "larger than expected number of entries" is surely a sign of success. The main repositories are held by dioceses, historical societies, colleges and universities, museums, religious communities, parishes, tribally affiliated institutions, and federal records agencies.

As with the Midwest Guide, an historical survey is provided for each order, each parish, each mission, each diocese, etc., which is very helpful for placing documents in context. The Official Catholic Directory still serves as the basis of institutional identification and history. There is some redundancy of information from location to location. This is a benefit, however, for, as Mark G. Thiel states in a preliminary report, the redundancies "illuminate administrative relationships and document flow [among] dioceses, local churches, allied church organizations, and civil authorities that [have] impacted Native American communities." Those communities are richly referenced throughout the new Guide. One cannot name all the many dozens of tribes included in this Guide. Just turn to the index to find them, from Acoma to Zuni, in all of the fourteen states surveyed.

Some states have more repositories than others, e.g., 130 institutions in California. Arizona (29/9%) and Washington (35.8%) have the richest resources; however, all have something worthy of mention. Here are some of the archives that especially caught my eye:

Alaska -- The Alaska and Polar Regions Collections, Elmer E. Rasmuson Library, University of Alaska-Fairbanks has collections of Native oral histories, manuscripts, and photographs. At the U.S. National Archives and Records Administration, Pacific Alaska Region, Archives Branch, we can learn quite a bit about Alaska Native history -- Eskimos, Aleuts, Tlingits, and the various Athabascan tribes, etc., even if the Catholic-related materials amount to but a "scant" portion of the total holdings. We learn more about the archives of these established, well-funded, non Catholic repositories than we do about Church repositories, like the Diocese of Fairbanks, which say little about specific holdings.

Arizona -- The Diocese of Tucson Archives and Library seems a rich resource, with its special collections regarding, e.g., the church of San Xavier del Bac, mission organizations, the evangelizing padre, Eusebio Kino, S.J. The scholar, Father Charles W. Polzer, S.J., has also deposited an archive in the Diocese Library regarding the Catholic-Indian relations in the region. These, in addition to the usual listings at diocesan repositories: Bishops' Papers, Sacramental Records, Parish Files, Newspapers, School Records, etc. The Special Collections Department, University of Arizona Library in Tucson holds manuscripts -- letters, reports, papers, diaries, government decrees, military and monastery records, finances, and so forth -- dating to the 1600s, in Spanish, English and Latin: accounts of all aspects of Catholic Indian relations in Arizona and the Southwest region as a whole, especially the Jesuit and Franciscan endeavors throughout the Sonoran area. These are complemented by the Library and Archives, Arizona Historical Society, Southern Division, also in Tucson -- with manuscripts dating to the late seventeenth century, including maps. In addition, the Archives, Arizona State Museum, University of Arizona, Tucson, seems especially promising, with its sources on folk Catholicism among the Tohono O'odham, Pima and Yaquis of the area, as well as the Pueblos of New Mexico. The anthropologist Edward P. Dozier's papers are among them. You could spend years in the repositories of Tucson.

In Tempe one would want to look through the Office of Ethno-historical Research, Arizona State Museum, with its 1,500 microfilm reels, documenting the history of the Southwest relations between Euro-Americans and Indians in the northern borderlands of New Spain -- dating to 1520!

St. Michael's Mission has Navajo Census Records dating to the late nineteenth century, parish files, photographs, scrapbooks, and other personal manuscripts.

California -- The 21 Franciscan missions of California and their asistencias are amply documented in archives throughout California -- their history, architecture, economy, demography, and their heritage to the present. Even though much has been written about these missions, there is always more to find in these archives. One can turn to the Bancroft Library, University of California -Berkeley, which contains documents from 1523 to the present. Or to the Huntington Library, San Marino, with correspondence, diaries, land deeds, newspaper clippings, proceedings, photographs, sacramental records, maps, sketches, and other source materials regarding the Mission Indians of California. Or you can go to La Purísima Mission State Historic Park in Lompoc, Ca, which commemorates the mission where in 1824 the Chumash and their Indian allies from other missions revolted against Spanish rule. The San Diego County Historical Society Research Library includes extensive photograph collections, 1884-1948, regarding the missions of the area. See, too, the California Pioneer Society, Alice Phelan Sullivan Library in San Francisco, for several thousand images -- paintings, prints, postcards, etc. -- of Native Catholics from Mission Dolores. San Luis Obispo County Historical Society contains materials regarding land claims of the Indians once housed at San Luis Obispo de Tolosa, dating to the Mexican era. The University Archives, Orradra Library, Santa Clara University, has extensive holdings regarding Santa Clara de Asís Mission and other California missions among the Miwok and Ohlone Indians (and also -- surprisingly -- materials from the Jesuit Alaskan missions among Eskimos and Athabascans).

I can attest to the value of the Diocese of San Bernardino Archives. One can see from the Western Guide that there are several folders from the various tribal missions of the area (Morongo, Pala, San Ysabel, Santa Rosa, Soboba, Torres-Martinez, Yuma, etc.) What the Guide does not tell us -- it cannot tell us -- how vibrant these folders are. As with any archive, you have to go there and peruse, in order to find out.

The same is true with the Diocese of San Diego Archives, regarding Pala, Pechanga-Temecula, Rincon, Santa Ysabel, etc. I know that these are superb resources, because I have looked them through; however, they seem bland on the Western Guide page. Now, I cannot even be sure where they are housed. Have they fallen into disorder, where they were once tended so carefully by Sister Louise LaCoste, C.S.J., Archivist, Diocese of San Diego? Now they seem obscured at the Diocese of San Diego Pastoral Center.

Colorado -- The U.S. National Archives and Records Administration, Rocky Mountain Region, Archives Branch, in Denver, has but small Native-Catholic content, but can provide the historical context regarding Indians of the West in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries -- especially in relation to the U.S. government. There are plenty of materials on agencies, schools, superintendencies, etc.

The American Music Research Center, University of Colorado, Boulder, has a collection regarding California Mission music, used for a book on the subject, published in the 1970s.

Hawaii -- The evangelization of Native Hawaiians is still relatively undocumented, but some information can be found at the Diocese of Honolulu Archives about Catholic Indians from West coast fishing tribes who have lived in Honolulu since the early nineteenth century.

Idaho -- The Diocese of Boise Archives refer to the tribes of the mountains region -- Coeur d'Alene, Salish, Kalispel, Spokan, Nez Perce, Kootenai, and others -- from the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

Montana -- The Tekakwitha Conference National Center in Great Falls -- which has as its goal the inculturation of Catholic tradition among American Indians across North America -- has its archives administered by Marquette University. Rather than traveling to Great Falls, scholars should see the online descriptive finding aid. The Diocese of Great Falls-Billings holds the nineteenth- and twentieth century records of St. Labre School, Ashland, where Crow and Northern Cheyenne Indians have attended. The repository serves as a kind of archive for the two tribes as well as for the Catholic Church, with board minutes, student records, publications, photography, religious community files, oral testimony from tribal members, and scholarly manuscripts all bearing witness to the Catholic educational experience there. Little Big Horn College Library Archives, Crow Agency, has a Crow Catholic Research Collection, with relevant copies of documents from the BCIM files at Marquette, Gonzaga University, and other places, with a focus on the Crows, plus audiotapes and other reminiscences by Catholics and Crows. The Diocese of Great Falls-Billings Archives has photographs of Assiniboine, Métis, Atsina, Siksika, and other Indians, plus parish records from more than a dozen missions and parishes. The Diocese of Helena Archives, also has extensive holdings, catalogued according to the usual diocesan rubrics: Bishops' Papers, Sacramental Records, Photographs, Scrapbooks, Video Recordings, Parish Records, Personnel Files, Religious Community Files, and Diocesan Newspapers. The Research Library and Photo Archives, Montana Historical Society, in Helena, has dozens of collections bearing on Catholic Indian relations, including the letters of Reverend Joseph M. Cataldo, S.J., Pierre-Jean De Smet, S.J., audiotape interviews of Native Catholics, such as the Blackfeet, and a photograph collection.

Nevada -- The Diocese of Reno has materials regarding Washo and Paiute Indians who attended the Carson Indian School.

New Mexico -- Santa Fe and its environs possess an abundance of repositories with outstanding collections regarding Catholic-Indian relations.

The Archives of the Archdiocese of Santa Fe, I can attest, is one of the great diocesan storehouses, with the bulk of materials dating from the 1850s: announcements, correspondence, reports, journals, sacramental and sodality records, including materials from John Baptist Lamy and his successors in the bishopric. The accounts of the New Mexico missions go back further to the Franciscans of the eighteenth century and even before the 1680 Pueblo Revolt. Sacramental records - noting births, baptisms, marriages, deaths, burials, etc. -- exist for all the Pueblos. The twentieth century documents tell the story of Pueblo Catholicism, village by village, church by church, with vivid primary documents regarding the adjustment and contestation between Church and Pueblo.

This archive is supplemented by the Fray Angélico Chávez History Library at the Museum of New Mexico in Santa Fe. This late Franciscan historian's library has collections of manuscripts regarding Catholic-Indian relations from the colonial era of New Spain to the recent past. The rich array of resources includes devotionals, prayer books, and the W.P.A. New Mexico Collection from the 1930s.

The New Mexico State Records Center and Archives in Santa Fe has excellent holdings regarding Catholic-Indian history -- various collections of historical documents dating to the sixteenth century, both originals and copies (e.g., on microfilm). Portions are available online. Consult oanm@unm.edu to peruse the contributing repositories in the Santa Fe - Albuquerque area: the Center for Southwest Research (University of New Mexico), the Fray Angélico Chávez History Library (Palace of the Governors), the New Mexico State Records Center and Archives, and the Rio Grande Historical Collections (New Mexico State University).

The Golden Library Special Collections, Eastern New Mexico University, Portales, holds some oral history cassettes and writings, which may shed light on Pueblo Catholicism in the Santa Fe Archdiocese.

When one sees mention of St. Augustine Church, Isleta Pueblo, one cannot help but note the gaps in archival records between 1680 and 1710 -- the years following the Pueblo Revolt of 1680 -- and also between 1965 and 1974 -- when another, unbloody but still fierce revolt separated Isleta from the Archdiocese of Santa Fe over the issues of syncretism and caesaro-papism. It would be interesting to see what documentation, if any, exists of the 1960s dispute and its eventual reconciliation.

In Albuquerque the Center for Southwest Research and Special Collections in the University Libraries of the University of New Mexico contains transcript collections that are appealing for someone interested in Indian oral histories. They contain hundreds of reel to reel recordings and transcripts from tribes throughout the Southwest and beyond on topics far and wide: boarding schools, inter-tribal contacts, Catholic development, legends, missionaries, and other aspects of history and culture, from Indian points of view. The Maxwell Museum of Anthropology, University of New Mexico, contains extensive archaeological and ethnological field notes.

The Diocese of Gallup Archives contains Bishops' Papers, including those of Bishop Donald Edmund Pelotte (of Abenaki descent -- often called the first American Indian bishop in the U.S.), 1986-2000, including his relationship to the National Tekakwitha Conference. There are also sacramental and parish records regarding Navajos, Apaches and Pueblo Indians.

The Branson Library, Archives and Special Collections, New Mexico State University, Las Cruces possesses intriguing holdings regarding Southwest missions, including 720 reels of microfilm from the Archdiocese and State of Durango in Mexico, regarding colonial outreach and administration of the Pueblos and other Indians in what is now the United States.

Oregon -- The Archdiocese of Portland Archives have extensive holdings, dating to the nineteenth century: Bishops' Papers, Sacramental Records, Parish Files, Photography, Priests' Papers, Women Religious, Community Files, Archdiocesan newspapers. These are supplemented by the Oregon Historical Society Research Library in Portland, with manuscripts and oral history audiocassettes, and other papers concerning Catholic-Indian relations.

Texas -- The Benson Latin American Collection, University of Texas at Austin, holds archives like the Carlos Castenada Collection regarding the Catholic heritage in Texas, including that of Indians. The Catholic Archives of Texas, Austin, has collections on the missions to Indians in Texas, seen in the larger context of New Span's religious expansion and administration. The University of Texas at Arlington Libraries has some mission manuscripts in Special Collections. Likewise at the Center for American History, Research and Collections Division, University of Texas at Austin. In all these places we find materials regarding the Tejas, Caddo, Comanche, Karankawa, Coco, Tonkawa, and other Indians. Indeed, one is amazed at how much is available in these historical archives, because Texas now has a limited number of Catholic Indian communities. The Texas Catholic Indian tradition is largely defunct and yet here are all these overflowing archives, not only on Texas Indian Catholicism, but also the greater project of Catholic evangelization throughout New Spain.

The Archdiocese of San Antonio has several repositories -- such as the Bexan County Courthouse, Spanish Archives Department; the Daughters of the Republic of Texas Library; the Institute of Texan Cultures Library, the University of Texas at San Antonio, etc., regarding Spanish missions in the area: Nuestra Señora de la Purisima, Conception de Acuña, San Francisco de la Espada, San José y San Miguel de Aguayo, and San Juan Capistrano -- which are of historical if not contemporary importance.

The Diocese of El Paso oversees Ysleta del Sur Pueblo and has some documents on these Tigua Puebloans, who abandoned their homeland along the Rio Grande in New Mexico after the Pueblo Revolt of 1680, in order to remain faithful to the Spaniards at El Paso.

The United States National Archives and Records Administration, Southwest Region, Archives Branch, in Fort Worth, Texas, may have only scant materials directly concerned with Catholic-Indian relations, but the greater historical documentary context exists for the southern Plains and beyond. There are materials not only for the many Indian nations of Indian Territory (now Oklahoma), but also historical data on Indians throughout the whole western region, from Washington to California.

The Diocese of Laredo, founded in 2000, has recent documentation regarding the Texas Kickapoos living at Eagle Pass, Our Lady of Refuge parish. This is a new wrinkle on Catholic Indians in Texas.

Utah -- The Ministry to the Intermountain Inter-Tribal Indian School, Office of Native American Ministry and other holdings are found at the Diocese of Salt Lake City Archives. The Marriott Library, Special Collections, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, holds oral history archives, including interviews with Catholic Indians and missionaries in the American Southwest.

For those interested in genealogy, the Church of the Latter Day Saints' interest in the world's genealogical heritage is in evidence at the Family History Library, Genealogical Society of Utah, in Salt Lake City, which contains voluminous records -- around 200 reels of microfilm, 1694-1990 -- on Catholic parish records throughout the United States, including, e.g., Indian missions in California.

Washington

The U.S. National Archives and Records Administration, Pacific Alaska Region, Archives Branch, Seattle, holds data from the greater Northwest: e.g., the Blackfeet Agency in Montana, the Chemawa Indian School in Oregon, the Fort Hall Indian agency in Idaho, the Juneau Area Office in Alaska, etc. How directly relevant are these files to Catholicism? It is difficult to say, but the federal records are not to be ignored.

In the Archdiocese of Seattle Archives the usual categories apply -- (as they do for the Diocese of Spokane): Bishops' Papers, Sacramental Records, School Records, Photographs, Cemetery Records, Parish Files, etc. When one has performed research in such an archive, however, as I have, one can attest how useful and revealing their holdings are.

The Jesuit Oregon Province Archives, Foley Library Special Collections, Gonzaga University, in Spokane -- constitutes an immense resource for the northwestern states, comprising dozens of collections, not enumerated in the Guide, but the reader is told to go to the Gonzaga website, where they are described in a very helpful, orderly fashion. These are monumental collections. Would it be worth listing them more thoroughly in the Western Guide?

Wyoming -- The Diocese of Cheyenne has documentation regarding St. Stephen's Mission among the Arapaho and Shoshoni Indians, from the nineteenth century to the present day -- the bulk of which is housed now at Marquette.

Topical Observations --

Diverse readers will find the Western Guide (and its forerunners) useful. What particular use we make of it will depend upon our interests. What are we looking for? Geneaologies? Church histories? Linguistic records? Each person has his or her own agenda and motivations. Different archives will have their special appeal -- by geography, tribe, religious community, time period, etc.

The larger repositories -- associated with universities and historical societies -- tell us far more about their holdings, and they seem the most useful in searching for grand historical data. But the small church holdings - which consist mostly of sacramental records -- can be useful, too, and it is good to know that they exist, where they are, and how they can be reached. One should be reminded that most American Indian history is local, and if one is interested in a particular community -- its local history -- the finely tuned parish resources may be invaluable. Whereas most churches repositories may seem bland at first blush, now and again we run across something more immediately promising, e.g., at St. Francis Church in Whitewater, Arizona, Diocese of Gallup, among the Apaches -- which contains chronicles, correspondence, reports, photographs, clippings, publications, periodicals, and a memoir -- from the early 1900s onward.

Most of the cited repositories focus upon the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, as one would expect. Nonetheless, some items dating to the colonial era can be easily found as we have seen, and, e.g., in the microfilm collections of Spanish and Mexican manuscripts in the Albuquerque Bernalillo County Library System.

The Western Guide does well at pointing readers not only to locales on the map, but also -- as we have seen -- to online sites, e.g., the Online Archive of California. Another example: the Tumacácori National Historical Park in Arizona has an online database of sacramental records dating to the seventeenth century.

As we have noted, relevant photographs are available almost everywhere. In addition to those already cited, the Special Collections and Archives Department, Cline Library, Northern Arizona University in Flagstaff has a photograph collection regarding missions and mission Indians across the state of Arizona. See The Billie Jane Baguley Library and Archives, Heard Museum in Phoenix has a substantial photograph collection. The Photographic Collections at the Arizona State Museum, University of Arizona in Tucson has Rosamond Spicer's pictures of mid-twentieth-century Indians in the Southwest.

For those interested in Southwest mission architecture and restoration, especially those built by the Franciscans and Indian neophytes, see the Alexander Architectural Archive, University of Texas at Austin. Arizona State University's Hayden Library, Special Collections in Tempe, includes the Southwest Mission Architecture Collection. And the University of California, Los Angeles, Department of Special Collections, includes postcards of various missions in its photographic archive.

For those interested in particular religious communities, like the Jesuits or Franciscans, there are special archives devoted to their histories. The Jesuits have been particularly active, e.g., in the Diocese of Fairbanks in Alaska. One can track the Jesuits' activities in the California Province Archives in Los Gatos. Jesuit materials are also available at the Archivo Histórico de la Provincia de México de la Compañía de Jesús in Mexico City. These considerable holdings, of course, are in Spanish. In French, the Archives Jesuites, Province du Canada Français in Sainte-Jerôme, Quebec are also available. And in English, promising Jesuits

records regarding Maryland evangelism may be found in the English Province Archives in London.

Franciscans? Go to their Santa Barbara Province Archives and Santa Barbara Mission Archives-Library, which traces the history of Franciscan New World evangelization, from the 1520s to the present, including all the Baja and Alta California missions. This is a vast collection of high importance, very well catalogued, and even though scholars have mined it, there is always more to discover and interpret. These Franciscan repositories are supplemented by the holdings at the Donald C. Davidson Library, University of California, Santa Barbara.

If we think that the archives list too heavily to the male side -- all those priests, friars, bishops, etc. -- there are some archives where we can locate the histories and impressions of women, especially female religious: e.g., the Sisters of St. Joseph of Carondelet, in the Library and Archives of the Arizona Historical Society, Rio Colorado Division, in Yuma, Arizona. Therein we can find accounts, memoirs, correspondence and diaries, from the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. These sisters seem to be especially cognizant of their duty to preserve records. The Los Angeles Province Archives in Los Angeles contains more than a century (1870s to the present) of manuscripts regarding their educational endeavors among Indians of the Southwest, e.g., at St. Boniface Indian Industrial School in Banning, California, and the St. Thomas Indian Industrial School in Fort Yuma, California. For those German-readers, as well as English-speakers, you can learn more about the activities and observations of the Sisters of St. Francis of Penance and Christian Charity -- active among the Oglala and Brulé Lakota Sioux in South Dakota, from the 1880s to the present -- at the sisters' Sacred Heart Province Archives in Denver, Colorado.

If one is interested in particular persons -- priests, sisters, Indians, etc. -- the Guide and its index can tell where to find materials regarding them. The Harold S. Colton Memorial Library, Museum of Northern Arizona in Flagstaff has the papers of Father Berard Haile, whose ethnological writings on the Navajo Indians were a high water mark of cultural, religious and linguistic sophistication. Haile's materials are also among the Franciscan Papers at St. Michael's Mission on the Navajo Reservation in Arizona, where he served for many years. The Special Collections Department, University of Arizona Library in Tucson also holds some of Haile's papers, and so does the Braun Library, Institute for the Study of the American West, Autry National Center, at the Southwest Museum of the American Indian in Los Angeles.

As a scholar I have been especially interested in Indian responses to and engagement in Catholicism; therefore, I look for examples of Indian agency located in these sources. By that I mean that there is an overflowing amount of information about Native history from the non-Indian point of view. I want to know more about what Indians have thought and done, from their perspectives, in their words, in texts and testimonies of their own making: their arts and artifacts, their correspondence, their publications, their public speeches -- taped and transcribed -- and so forth. Does the Western Guide let scholars and others know where these primary Indian sources can be found? Yes. Oral history collections, e.g., at the Center for Southwest Studies, Fort Lewis College, in Durango, Colorado, can be a boon. The Center for Oral and Public History, California State University, Fullerton holds archives regarding St. Boniface boarding school and other matters of twentieth-century adjustment for the descendants of California Mission Indians. One wonders what is in the one folder at the Gilroy Museum in Gilroy, California, regarding Ascensión Solórsano, an Ohlone Indian (1845-1930) -- born and buried at San Juan Bautista Mission. It is a good bet to consult tribally affiliated institutions. Barona Cultural Center and Museum,

Lakeside, California, is an example of a tribal repository with Catholic Indian content, where one may find examples of Indian testimonies. The Cupa Cultural Center, Pala, California, contains eighteen recorded interviews with elders, 1970s-1990s, in which they speak of their Catholic identity, among other topics. I wish I had known of this resource when I visited the Cultural Center in 1992 and interviewed some of the same people.

The Western Guide will help us learn more about urban Indians as well as those on their reservations. The Diocese of Phoenix Archives, the Office of Native American Ministry, contains materials that help tell how the Archdiocese of Los Angeles responded to the cultural shock of urban Indians -- some descendants of the California Mission Indians, but most from around the country (e.g., Lakotas from South Dakota), who arrived in the city as a result of the United States Indian Relocation program beginning in the 1950s. The Catholic Indian Club in L.A. tried to address their needs, beginning in the late 1950s. From 1989 to the present Rev. Paul Ojibway has conducted an urban ministry to some of the 25-40,000 Indians in the archdiocese. As a result, at the Archdiocese of Los Angeles Archival Center you can find not only voluminous manuscripts and sacramental records dating to the late 1700s, but also some contemporary urban materials. The Archdiocese of Denver Archives also has recent data on the local urban ministry to Catholic Indians, as well as historical manuscripts.

Mark G. Thiel's interest in Indians throughout the Western hemisphere shows through in the archives regarding recent Indian immigrants to the U.S. from Mesoamerica -- particularly the Mayans from Guatemala, found since 1994 under the Maya Pastoral Project in Mesa, Arizona. Thiel estimates that 150 200,000 Mayan Catholics now live in the U.S., including 150 catechists and at least one priest. Mayans are also ministered to in Indiantown, Florida, at the Hope Rural School. In addition, the Yaquis from Mexico have made their homes in Arizona, around Tucson and Phoenix, for more than a century, and created for themselves an independent Yaqui Catholicism. One can find Yaqui documentation in the archive of Our Lady of Guadalupe Church in Guadalupe, Arizona, as well as in several repositories in Tucson.

The Western Guide is a daunting, inspiring text. When I look at the fabulous collections of manuscripts, easily available, about the development of American Indian Catholicism over the centuries, I realize -- comparatively -- how little research I did before writing three supposedly "monumental" or "definitive" volumes on American Indian Catholicism. I took ten years. I should have taken another ten, at the least.

Future researchers, however, should be motivated by how much there is still to learn. None of the Guides produced by Marquette can tell them exactly what awaits them in these archives; however, there is a world of knowledge, awaiting exploration. In the end, I would advise, you have to go to these places and learn for yourself. Here is a new Guide to point you toward the troves. It is a kind of treasure map. Now, intrepid investigators, pack your bags and your laptops and begin your journey.

Christopher Vecsey

Charles A. Dana Professor of the Humanities

Director, Native American Studies Program

Department of Religion, Colgate University

new2006/rev2017